Voidheart Symphony (Part 2)

Become the revolution that your community needs

This is the second part and conclusion to our Voidheart Symphony critical analysis. You can find part one here.

5. Disassemble Engine

Games have a flow, which, when you hit, the game pretty much runs itself. It is extremely satisfying. After examining the interactions of game elements, we single out the most important - the one that sets the pace of sessions, or even campaigns. We focus on how that engine works, how it makes the game move along, and what to do to make it do what you want to do - and how to keep it running clean.

LudoVoidheart Symphony is, like its predecessor Rhapsody of Blood, known for its amazing boss fights. However, that is not the engine; the engine is what gets you there and keeps delivering fantastic and meaningful showdown after fantastic and meaningful showdown.

This game has a quite sturdy redundant series of systems; we have had here all kinds of engines, even games without them, but not one organized like Voidheart Symphony. While similar to redundant engines with things like support and backup engines, it reminds me more of biological homeostatic configurations than the awe-some churning of a complex machine doing what it is designed to do.

To better communicate this impression, I would call this organization of systems and engine configuration nested. The systems border into each other, but they have their own layers of systems. As required and/or desired, one shifts between layers almost effortlessly. This type of configuration really shines with the high variability of systems, but each as approachable as possible.

Let’s get concrete.

The Investigation cycle is the recommended starting point because it is the first layer of the engine nest. You start with a Vassal threat that has affected all of your lives; develop further connections, then are introduced to a new Vassal that threatens those. The Investigation cycles regulates itself through the progress of the investigation, The Grind putting pressure in the mundane lives and a clock tracking the progress of the Vassal against the player characters. You make progress, but there are also always new Vassals to exploit the Castle.

The Pressure Of Urban Living In Post-Neoliberal Capitalism is another engine keeping you tangled into the mundane muck rather than disappearing in the imaginary of the impossible of the Castle. The turmoil of City life is regulated by systems that draw from Resistance and Ironsworn: the psychopolitical eats your health, reputation, security, finances and sense of community. This keeps the pressure on, forcing you to pace yourself, take care of your life of the City and look for solution in the Void — at the same time, ignoring the Vassal actions and failing investigations only gonna increase your precarity.

The Condition systems limit how much you can delve into the Castle, force you to be cautious in your rebellion within the City and keeps pushing you to form meaningful relationships — Covenants — and take care of yourself and others.

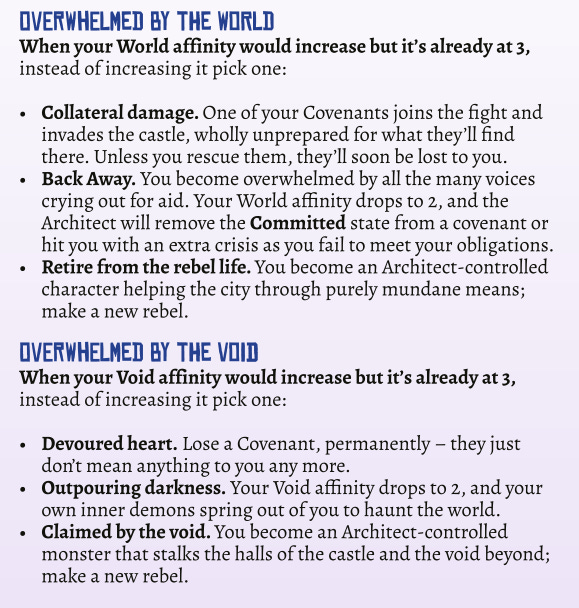

The City/Castle and World/Void duality is the top layer of nested engine. These are two powers that let you rebel against the hierarchy of the Castle and the Vassals — all while taking care of yours. These forces may help you, but are in tension with each other — which then allows the duality to work as an engine. You grow in power, but you can also be overwhelmed by these powers. And believe me, you will at least once a campaign, and is very likely to be a dramatic climax for your character. This layer keeps you getting more powerful, but also gonna hurt the people around you or consume who you are.

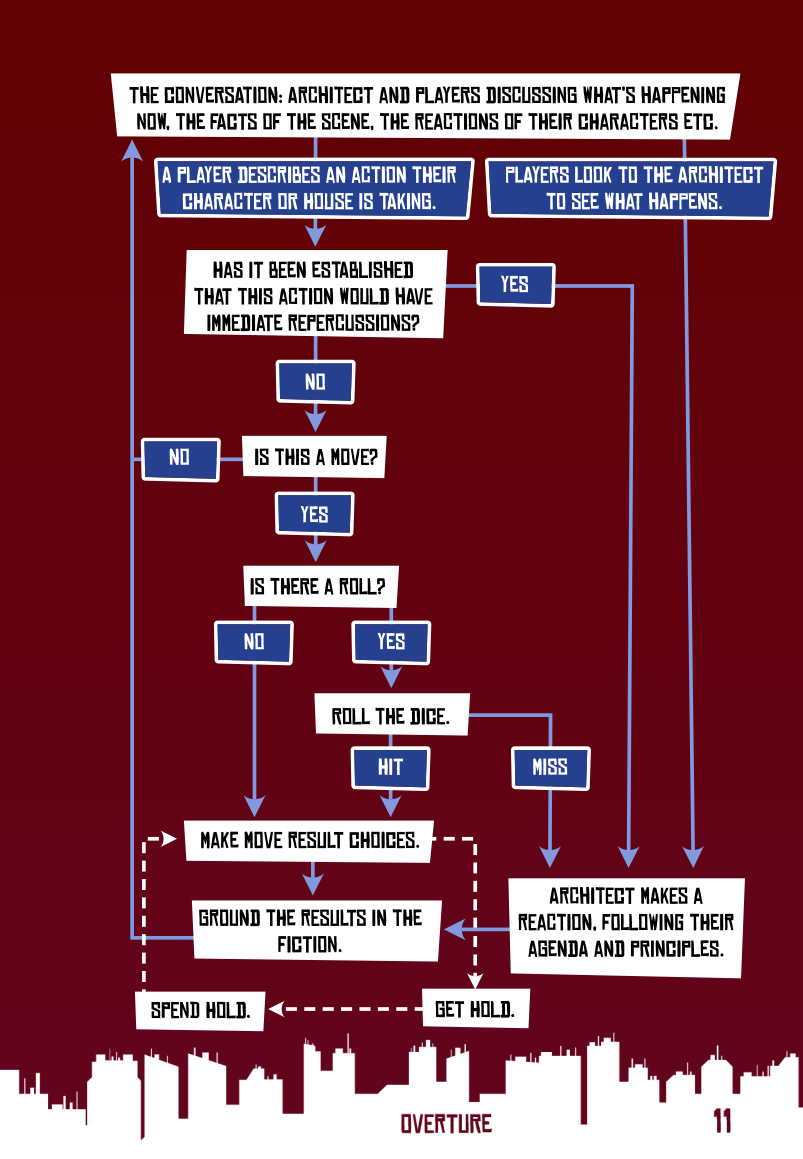

What are the benefits of this engine structure? Well, a problem with roleplaying games that have some kind of resolution mechanic is that things just seem disconnected from the ongoing narrative discourses, from “what happened” in the fiction. PbtA tries to connect these with “fiction driven” doing-the-thing-to-do-the-thing; however, as it is a framework rather than a system, the actual relationship to ongoing narrative discourses at the table is purely ideological, tethered together my a meta/super structure. At the end of the day, it comes all to arbitrary calls outside of any ongoing discourses and other systems — is it really fiction-driven or driven by the enforcement of an ideology of what fiction should look like? Unless one gets freaky with it, PbtA-as-system only really manages the most obvious and immediate cause/effect causality as fiction-driven.

As I mentioned previously, this nested configuration reminds me of biological and biochemical systems. It gets freaky with it. The redundant layered systems are sturdy; they shoulder the deluge of precarity that the game is about quite well, without getting in the way of you doing things; at the same time, they constantly add new stressors into the engine. Alas, the systems are quite sturdy; you may take quite the beating and be able to move stress around. But you get the feeling that all these aggressions accumulate, and you can still keep going. It works.

Until it does not. And that is when all the stress-management and stressor-containing elements collapse; it never feels arbitrary. Every risk you knew you should have been cautious about, all those relationships you neglected, the rest you did not take, your haste in the investigation. It is pretty clear that you can trace what happened to what may be campaign-long history of decisions at the table; it is fully harmonized with the discourses of this art form in play.

Now that is what I call fiction-first.

BradMy players, fell in love with this engine, and as someone who loves duality as a theme in campaigns, its no wonder I too became a Voidheart Symphony Sicko. The system never once feels arbitrary or unnecessarily cruel, it puts most of the risk on the choices a player makes and I love that. There is something that is so rewarding to see players running the math on a risk and deciding that risk is worth it, even if it bites them later. Voidhearts rules cycle is so satisfyingly written, designed, and explained, that my players were itching to get back to it.

6. Essentials For Session One

So, you got this game, you are going to play it, but you don’t have the time to read everything. Or even worse, yourhave read it and now it is all jumbled together. Here we break down the things that you absolutely want to try to get right and/or hit during your first session, so you get the feeling of what makes this game stand out from similar art.

LudoThis is embarrassing.

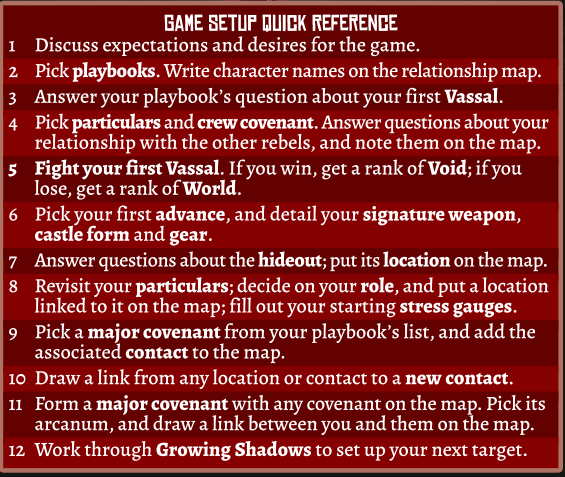

Not only the guidelines for first session make you go through every step in an easy manner that requires you absolute zero knowledge of the rules before, it guides you through all the bits that you need to experience to see the potential of Voidheart Symphony. Entrust 2-3 hours to this game and you will know if it does what you want it to do.

You gonna do a whole investigation! You are going to meet Covenants! You are gonna get your corner of the City! You are going to go into the Castle and kick off immediately with a Boss Fight! You are going to enact change to the City through the Void and you gonna position yourself to fight another tyrant.

It is the perfect bite-size experience. More sessions gonna be a scale-up of those connections to Covenants, exploration of the Castle, fighting Vassal bosses and their Knight mini-bosses and running investigations of increasing complexity. Absolutely recommend to kick off every campaign like this.

However, there are some caveats that come from the experience of having done so multiple times.

One may be tempted by the list of moves to want to try them all. It is better to use moves sparingly during the first session — or at least, not combat moves. In the same vein, one may be conservative in the exploration of the Castle and building up to the boss fight. That tends to bog down and can lead to loss of focus in unexpected ways; instead, I would suggest characterizing the Vassal and the characters within the City, and accelerating within the first foray into the Castle straight to fighting the Vassal. Rather than using the Exploration moves, run a short scene for each character across the Castle and then have them face the Vassal. When they tell you to jump right to the end, jump right to the end!

If you are going to do prep, I would recommend you check the Covenants in advance. The only moves really worth familiarizing ahead will be the Confrontation Moves and the weapons — as those are the only moves you should be using this first investigation.

BradIn addition to the very good summation above, print out the cheatsheets, you should do this for every single PbTA lineage game, but especially here and you will have a great time.

7. Playing The Game Wrong

Games are played wrong. Rules will be misunderstood, interactions will be confused, the importance of certain tech disregarded; etc. This is good, and it is good to acknowledge for: you cannot have the designer at your time, and even if they were, they would be just another player - and entitled to play it wrong. After identifying stress points of the game, things that don’t connect that well, we think of the things that are more likely to be (our have been) “played wrong”. What happens when you forget a line in page 273 clearly saying this is impossible?

LudoIt is weird to think about this, having played every single version of this game that came out during development; there is no possibility that has not warped my perception about Voidheart Symphony’s stress points.

I think the weakest point of this game may be playbooks; they are fine, but considering how much the game has changed and what playbooks do for this game, I cannot but wonder if they are a vestigial feature, preserved because they are expected to be there and do what they are intended to do well enough.

Whoever, if you slide in and you are in PbtA mode, and just circle which moves and playbooks this game has, this can be easily missed.

The purpose of a playbook in Voidheart Symphony is to be pierced, a cocoon to be split open by the accumulation of Covenants, development of the City and torn asunder by the Void and the World.

It is a known limitation of orthodox PbtA that characters tend to quickly outgrow their playbooks and how awkward progression can be, especially of the same playbook played through multiple campaigns. Voidheart Symphony is aware of this limitation and makes it a feature, by using playbooks as the ceiling of realism characters break through and quickly outgrow.

Does it work? Quite well. Could there be a better solution? By the rest of the game and the design process, I have no doubt there could be something even better. But art is not to be perfected, it is to be done with at some point — especially art such as tabletop roleplaying, which is always unfinished. What one must take from this, is that it is quite easy to overestimate the importance of playbooks and downplay that of Covenants.

Another tension point may be campaign pacing. Voidheart Symphony shines during the sweet spot of orthodox PbtA (4-12 sessions) campaigns duration. However, the City, Castle, Covenants and Investigations benefit from increasing complexity in every repeated play cycle; this suggests to me that there is really a special side to this game — that like other Legacy games — that really needs a longer campaign to come through. But as mentioned above, not only are playbooks purposefully limited in development, Overwhelmed By The World/Void are some of my favorite parts of this game but they are really something you get diminished returns from hitting multiple times during play. I really want to bring this up for a very long campaign, but this may have to require the expectation to rotate and retire the cast. The Covenant system can easily be used to facilitate this.

Finally, it is very easy to have a City phase and a Castle phase when running an Investigation and that can become a habit and expectation hard to break once it settles. The game really shows its best side when you have a constant interplay between the City/Castle; don’t let rigid boundaries form between your perception of both worlds.

BradSo, this game definitely scratched my normal test group’s itches, and in full disclosure, we did only play a small amount of it, but I do think Ludo’s above would ring true over a longer-term campaign. I personally heavily agree that the playbooks could use some love, and if I was going to run a longer-term campaign, I would definitely invest a lot of time in making sure the covenants were very dynamic as characters, make the players invest in them and I think the engine will sing.

8. What to Steal

Experiencing good art is the most important step in making good art. We look back at the things that worked and did not work about this game, see what we learned for design work, interesting tech and just a general overview of things that we will take from this game and bring into others. Or more honestly: since many of us may not play this game and we have it in our library, this way we can get some use out of it.

LudoSteal this game politics, steal its hope and steal its spirit.

Designers with an interest in PbtA, Voidheart Symphony joins Flying Circus and Fellowship 2e as very special games that show the potential PbtA-as-Framework still holds.

I have a hard time design for this lineage of game, not because it is inaccessible, but because they tend to be so tight and satisfying as it is. If you are not as intimidated as I am, Voidheart Symphony is covered by the RR&D Community License.

BradVoidheart is a game that I struggled to critique rather than review, because it is so solidly done in so many aspects. For that, I will apologize to our honored readers. However, you should steal as much as you can and if you feel bold enough to dream of a revolution, maybe take a spin on the community license.